Jesse Howard, Fulton, And The Arguments That Became Art

By Thomas K. Riley

He was named one of the ten most important folk artists in America before his death, his works hang in the Smithsonian and around the world, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes described him as the “Grandma Moses of print culture;” yet, few in his hometown of Fulton would remember Jesse Howard as anything but an eccentric crank. As the years have passed, Howard is more renowned for his art outside of Fulton than within it, which might just be appropriate because it was Howard’s uneasy relationship with this community that inspired his best work.

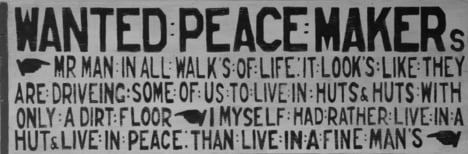

Jesse Clyde Howard was born on a dirt floor in a one-room log cabin in Callaway County in 1885. The youngest of ten children born to farmers, Howard attended school for only three months a year and dropped out after the sixth grade. At the age of 14, Jesse headed out west where he took odd jobs from Montana to California, and first encountered the homemade signs along the railroad that would eventually be the medium for most of Howard’s artwork. He returned to Missouri a few years later and married Maude Linton in 1916, the mother to his five children.

Howard was a typical Missourian in many ways-a farmer, handyman, conservative, and devoutly religious. He and his family lived on several farms-including one lost in the depression-before he purchased about 20 acres on the south side of Fulton along the old road leading to Jefferson City.

He called his homestead “Sorehead Hill.”

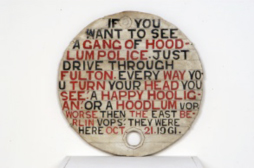

It was this property that eventually would be both the source of Howard’s troubles and the venue for one of the most important contributions to 20th century American folk art.

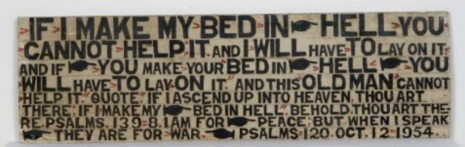

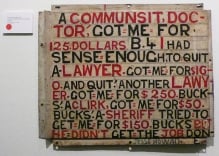

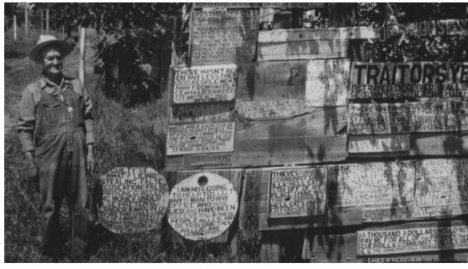

While Maude worked at the shoe factory, Jesse first started making signs in his fifties for good friend Ed Peacock, who held an annual show of old-time steam engines and farm implements that attracted crowds from across the country. Howard enjoyed the attention at these shows and eventually starting making his own signs, paintings, and models to display around his house. Having lived through the scarcity of the Great Depression, Howard re-used nearly anything he could find-attaching car door handles as knobs, using a shovel handle as cane, and transforming old metal and wood into models and paintings. Whitewashing its surface and then writing or painting in magic markers, in bold black and sometimes red lettering, Howard’s art always expressed his deeply religious and uniquely personal views. His first sculpture was a recreation of the gallows of Hamam, and he built models of biblical burial grounds across his property. Even though disputes with the Church of God Holiness ended his regular church attendance, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of his King James Bible and a tenuous grasp of standardized spelling.

As Howard continued to create, most neighbors failed to appreciate either his message or his art. Ultimately, it was this conflict between the individual and the community that gave rise to Howard’s prolific outpouring of work. One of Howard’s earliest pieces was a model airplane that he proudly displayed near the gate to his yard, but vandals destroyed the plane. In response, Howard created the first of his idiosyncratic signs of protest-an all-caps screed that spoke out against those who had wronged him.

The very people who rejected, and even stole or destroyed his work, became the focus of hundreds of signs, a typical one reading “SOME OF THESE CROOKS ARE SO HELLIFIED CROOKED THAT THE DEVIL WILL HAVE TO CUT THEM UP JUST TO GET THEM IN HIS FURNANCE.”

Howard continued to paint signs expressing his views on religion, politics, and the business and civic leaders of Callaway County. Vandals continued to destroy and steal the signs. Police continued to ignore Howard’s protests. And so Howard made more. This dialogue-between a proud and angry man and the skeptical public around him-would literally become his life’s work. When later asked why we painted his signs, he replied simply “I can’t speak what I want to sometimes.”

His neighbors were not impressed. In 1952, a petition was circulated to have Howard admitted to the Fulton State Hospital. Although the petition was rejected, Howard was concerned enough to travel two years later to Washington D.C. in hopes that his congressman could offer some assistance. Instead, Howard was summarily placed on a bus back to Fulton by the secret service-his faith in government unrestored.

Howard then continued his prolific creations not just in spite of the town’s resistance, but largely because of it. “Nobody likes me in this town. They don’t like me because I’m telling the truth on them,” he said. Howard eventually built ten buildings between the thorn trees and brush on his little farm, which he now called “Hells Ten Acres” and “The Suburbs of Hell,” to showcase his art, covering nearly every wall and fence with hundreds of signs-a homemade monument to personal expression that would later be cited as the inspiration for a new movement in folk art and print culture.

It was not, however, until 1968 that the art world began to take note of Jesse Howard with the publication of Art in America, which prominently featured Howard as a new type of folk-artist. Eventually, the faculty at the Kansas City Art Institute began visiting Howard and later purchased dozens of his works for what is now the largest collection of Howard’s compositions. By 1977, the Kansas City Art Institute had acquired enough pieces that they hosted a show featuring Howard’s art-the opening of which Howard described as “the best day of my life.”

Howard delighted in the attention of his visitors and continued to give tours of his property until his nineties, asking everyone to sign a guest book with their impressions. Artists, reporters, and students flocked to Fulton from across the country, and there they met the self-described man of “many signs and wonderers,” who would lead them around his farm using his old shovel handle as a cane and smiling his wide toothless grin-he had lost all of his teeth by the age of 35-Howard always part showman and part artist.

Howard’s works were later featured in a show at the University of Missouri-Columbia, shortly before his death, and several books on “new” folk or “idiosyncratic” art featured his pieces prominently. While Howard was keenly aware of the attention that came from afar, he remained equally sensitive to what he saw as rejection from his own community-a tension that always informed his work and was never resolved.

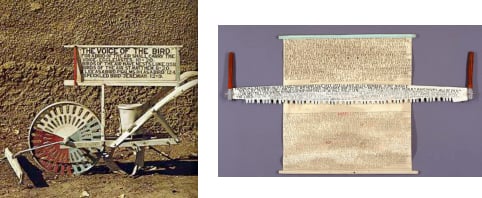

Jesse Howard died at Sorehead Hill shortly before Christmas of 1983, but the appreciation for his work continued to spread. In 1997, the Smithsonian acquired his piece The Saw and the Scroll. The Voice of the Bird was later donated to the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, and other works hang in The American Folk Art Museum and dozens of other museums around the country. In 2015, the St. Louis Contemporary Art Museum hosted Thy Kingdom Come, the first comprehensive museum survey of Howard’s art.

Even as Howard’s recognition has grown nationally, his memory in Fulton has faded. The road running past his house was renamed Signpainter, but the house itself and the buildings were torn down, his children moved away, and his works scattered across the country.

Perhaps it’s appropriate that one now has to look so hard for signs of Jesse Howard in Fulton. He became an artist because our community did not want to hear what he had to say, and his greatest works were a product of his one-sided conversation with our town. So, it’s important to his legacy and our history that we recognize his artistic contributions, even if we still don’t know quite what to make of Jesse Howard.